Life in Music

The song begins and without realizing it, you begin to sing along. You like to sing, even if your voice is not very good. So you sing when you are alone. You learn to sing through repetition and imitation. You don’t want to be the singer. You want to know what the singer knows. You sing because it feels good.

In 1978 you could browse through any teenager’s record collection in Forest Lawn and find three albums. These records were the cornerstone of a good music collection. Possessing them was a mark of the owner’s coolness. There were other albums between and around them, but the following three appeared without fail:

Led Zeppelin IV

Pink Floyd Dark Side of the Moon

Supertramp Crime of the Century

I remember seeing boys who had Led Zep logos embroidered on the backs of their jean jackets and wondering what “Zoso” meant. I was always fond of Zeppelin, but I never got totally into them the way I did with Supertramp and Pink Floyd. These albums I played religiously. I even made a point of listening to them through headphones on LSD so I could study them more closely. It was on acid that I discovered the cuckoo-clock sound that ends side one of Crime of the Century. I am baffled by the totemic status these albums had and wonder what their equivalents are today.[1]

In 1994 I was sitting in an espresso bar in Lucerne with a friend from Hungary. Her English was limited and we struggled to maintain a conversation. The cafe’s sound-system played Crime of the Century on CD. The crispness of the music was almost painful. I had not heard this album for at least twelve years and was not a little surprised by how annoying it sounded. I found Roger Hodgson’s warbling and the bright, melodic, piano flourishes distracting, like being attacked by a swarm of bees. It made me conscious of how much time had passed and how much had changed in the interval. I tried to explain to Sonia the role this music played in my life and describe the strange transformation that had occurred. “Theese museek,” she said haltingly, with a hint of sour-faced revulsion, “eet eese wary… SWEET.”

The change occurred not in the music, but in the listener. This fact amazes me, not because it means something as banal or obvious as “I can change,” but because it indicates that what we hear in music is never stable; that what is heard is heard differently by different people. When this happens, I have a split second glimpse of a world outside my subjectivity. It can be as simple as the difference between whether a song sounds happy or sad, complex or trite.

Imagine making the loudest sound you can make. Bare your teeth, loosen your tongue. Force air out of the lungs. Let this feeling lift you up. The chest, head and throat vibrate together. The voice emerges from the viscera. It feels good.

1999. I am back in Calgary for a visit after living in Montréal for eight years. When my Lebanese cab driver (who spoke an unaccented working-class Western-Canadian English eerily similar to my brother’s) determined that I was once a native, he asked me what high school I went to.

“Forest Lawn.”

“Forest Lawn?” he said doubtfully, glancing at me in the rear view mirror with one eye-brow raised incredulously. He looked over my faggoty clothes, my short hair, my nerdy glasses. “That’s a tough school.”

It wasn’t until years after I’d graduated that I learned that Forest Lawn, both the school and the suburb, had a bad reputation. Forest Lawn wasn’t tough in that urban city-center/gang activity/crack-house kind of way. It was more of a rural, trailer-park trash/Jerry Springer-style, conjugal violence sort of toughness. If I now consider drug use, vandalism and other minor felonies normal parts of growing up, it was because I spent my adolescence in Forest Lawn.[2]

In spite of its reputation, F.L.H.S. paled when compared with my earlier junior high school experiences at Ian Bazalgette (pronounced Bazal-JET by the teachers, and Bazal-GETTI — to rhyme with Alphagetti — by the students). The school was overcrowded: two-to-a-locker. My locker partners were always hoodlums. If I modeled my school persona after Marcia Brady, my locker partners emulated Charles Manson. My first partner, Terry Henderson, was the embodiment of pure meanness. His gang got into chain fights with other gangs on the roof of the gymnasium before later setting the same gym on fire (thus interrupting a full year of dreaded gym classes). Terry regularly locked his adversaries in our shared locker, serving the double purpose of scaring the shit out of both me and his victim. When Terry was pulled from school — presumably bumped to yet another fosterhome/detention center — he was replaced by Doug Herkel, one of the school drug dealers (and truth be told, a pretty nice guy). Our teachers had frequent and spectacular nervous breakdowns (but isn’t that normal for any school?). We tortured our alcoholic music teacher, Mr. Robinson, by locking his keys in a metal cabinet week after week. The only thing I remember doing in music class that was remotely musical (there were no instruments except recorders) was talking about bands with my fellow students during the long intervals when Mr. Robinson absented himself. The logos of AC/DC (the early Bon Scott version), Alice Cooper and KISS were carved a quarter of an inch deep into 47% of the dilapidated antique wooden desks at Ian Bazalgette. I never listened to these groups much, but if I had to pick a fourth album for my mythic list, it would be Highway to Hell.

The Greeks believed in a beauty so perfect that to gaze upon it would cause blindness, to hear it would drive a person mad. Our image of the power of the singer is that of sound waves breaking a champagne glass. It is the destructive power of beauty that fascinates us.

I listened to Dark Side of the Moon so much that I wore out one copy and had to buy another. My parents were hip enough that they listened to a lot of the same music I did. But their taste drifted more towards America and Southern California: Fleetwood Mac, The Eagles and Chicago. I only listened to music if it came from England. But there was some overlap. My dad was very excited when I first played Dark Side of the Moon for him. And I listened to Fleetwood Mac Rumours. I remember playing Christine McVie’s “Songbird”, holding my dog on the couch in the living room and crying my eyes out, thinking how someday my dog would die. I don’t think I was stoned.

This text is to some extent about embarrassment and humiliation. We all like to claim that “we-saw-that-group-when…” or “we-were-the-first-one-on-our-block-to-buy-that-album,” but how many of us really want to admit to the really icky stuff? Listen, the first long-playing album I ever bought was by The Captain and Tennille. I was smitten by the single “Love Will Keep Us Together” to the point where I felt it was time for me to make a major commitment. I remember that when you opened the gate-fold sleeve, you could see the Captain without his sunglasses! (One of the gimmicks of the group was that you NEVER saw the Captain without his sunglasses: a bit like never seeing the four lads of KISS without their make-up.) Anyway, the Captain had brown, sensitive, puppy-dog eyes that were painfully large, almost to the point of physical deformity. If anything, he resembled one of those weird, doe-eyed, children so popular in the ubiquitous kitsch paintings of the epoch. I speculate that the Captain had certain insecurities regarding his ocular endowment and hence, the shades. Incidentally, Tony Tennille sang backing vocal on Pink Floyd’s The Wall, another life-shaping album I listened to with a pharmacopoeia of psycho-active drugs playing bumper-cars with my neurons.[3]

Patsy Cline is singing a happy song, but the sadness of her voice cuts through the music. Patsy’s voice is serrated with pain. It rips through the meaning of the song like a saw-blade tearing a log in half. The content suddenly becomes doubled. It’s as if we’re looking through binoculars the wrong way: joy seems impossibly distant and remote. We stab at happiness from the heart of mean-spirited envy. But the knife blade always falls short of piercing the mocking target.

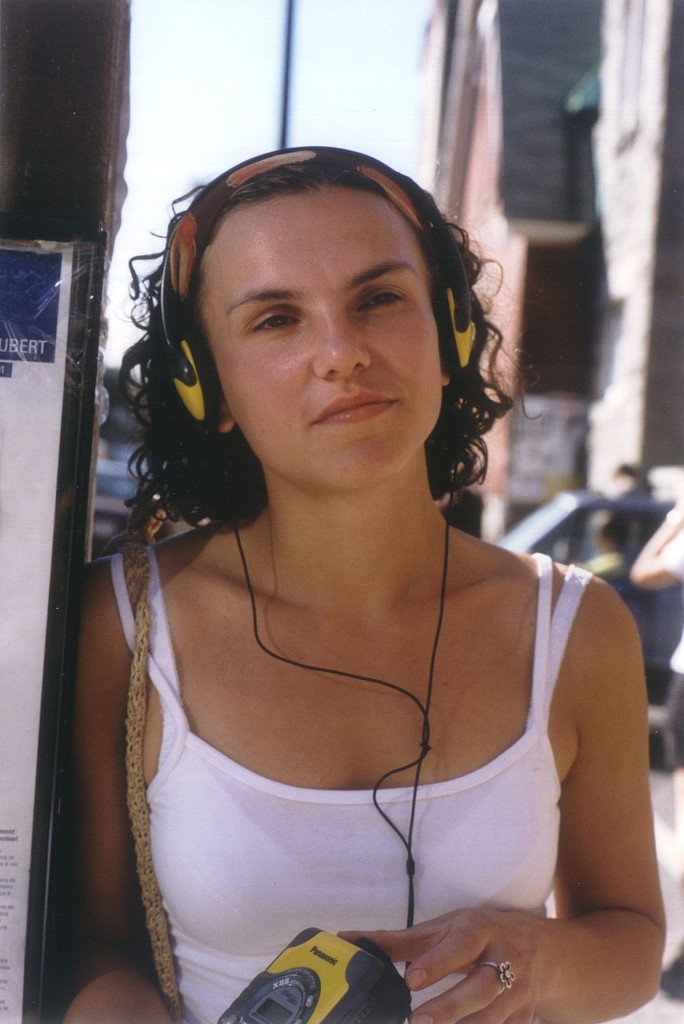

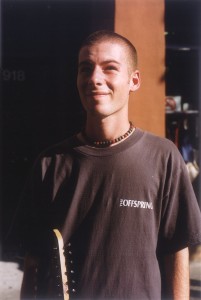

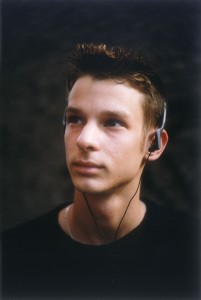

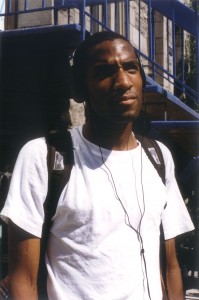

At the pool, the men all look the same when they are in their bathing suits. But when we get out of the water, go to the locker room and get dressed, our relationship to one another changes. We become coded as soon as we are clothed. When I see what you wear, I can begin to imagine what kind of music you listen to.

Music, more than anything else in our culture (with the possible exception of clothing), brings out our tribal nature. Walking to work two years ago, I noticed someone had spray painted a fresh “Led Zep” on the wall of a disused parking garage. What does it does it mean to paint “Led Zep” on a wall now? John Bonham has been dead since 1980; the group disbanded not long after. Instead of writing their own name, someone felt it was important to make this mark: writing a band logo on a brick wall. Yet the gesture is intensely personal; a declaration of one’s taste in music also expresses a social position and a philosophy towards life.[4] The degree to which we identify with bands, recording artists or certain musical genres is profound and complex. We can’t imagine someone identifying with, say, films genres, in such a primal way. Saying “I like westerns,” is not the same as saying, “I like country and western.” There are vast webs of associations that emerge from such utterances.

The singer sits hunchbacked on a stool. She seems far away, perhaps in a trance. Her face is in front of the microphone. Eyes closed, nose crinkled up, her mouth, open. The jaw pumps up and down with a muscular tightness. Now and then, she throws her head back violently, removing her hair from her face. When she is not singing, she turns away from the mike and breathes deeply. Her left arm jerks up and down, punctuating the downbeat with each descent. Fingers splayed. Her right hand sways back and forth, marking the tempo. Periodically her fingers curl, forming or releasing a fist. She draws her hands together in front of her chest, as if she is holding someone’s severed head between her palms. She lifts her chin. Her mouth forms a perfect O.

1997. I am sitting in a coffee shop in Calgary with a friend from the UK when the song “Dreams” by Fleetwood Mac starts playing on the radio. “My god,” he sighed, “ten years ago I was listening to this. Then my girlfriend played ‘God Save the Queen’ for me. The Sex Pistols changed my life.” Music can do things like that. It seems impossible now that Rumours and Never Mind the Bollocks were released the same year. Ten years later, in 1987, I found it sort of pathetic that people still dressed up as punks, as if they were trying to crash a party that had been over ages ago. Now, in 2000, punks have been loitering around for over twenty years. The squeegee-toting teenagers I see jockeying street corners between red lights are young enough that they could have had punks for parents. Punk is not just a style now, but a life style. Punks are a tribe; a social group with a history and a belief system all their own.

The t-shirt reads: “Become what you are.” It’s the slogan for a tattoo shop I visit and I like what it implies. It’s as if the tattoos are already there, under you skin, just waiting for a chance to bleed through and finally become visible to the outside world.

What is fascinating to me about squeegee punks, and any number of people who have tattooed and pierced themselves into the margins, is that they have willed otherness upon themselves. Growing up queer in the working-class (and reputedly tough) western Canadian suburb of Forest Lawn, I was very conscious of my difference from the start. I tried to will myself into normality, or at least into invisibility as a compromise. I am sure that this was also true of the South Asian immigrants who passed like shadows against the gray locker-lined halls. But here are these young white (and straight?) people who refuse to play the game. This is how I choose to understand them at least: that they have flushed much of western culture’s value system down the drain. I feel like going up to them and saying, “You can’t see it, but under my skin, I am tattooed from head to toe.”

I never really listened to punk in the late seventies, but preferred the more prog rock stylings of Yes and Genesis, or the full-on glamorama that was Bowie and Bolan. It is weird how strongly the budding proto-gays and lesbians of the seventies, who would blossom into queers in the eighties, were all fixated with Bowie and Patti Smith. One of my friends who was in a drug and alcohol rehabilitation program in the eighties told me that in all the straight groups sang Beatles’ songs, while the gays and lesbians performed Bowie medleys.

Now, I would never want to be accused of saying something as wrong-headed as “celebrities belong to the people”. But on the other hand, this text is partially articulating music for those who have always been presumed to be dumb and inarticulate: that faceless mass of listeners who we refer to more or less pejoratively as fans. I am not talking about music per se, but about how music is used. Although we love recording artists, we regularly amputate music from its maker and make it ours. This allows us the freedom to reinvest it with a whole new set of meanings.[5] How else can you explain why someone would write “Led Zep” on a wall today? How else can you explain why gays and lesbians were shattered when Bowie went from bisexual to straight at what was a pivotal and defining moment for the vilification of gays and lesbians.[6]

When we hear the voice, we move to a place without words. Time denies either future or past: we move sideways into this moment. Firmly and comfortably inside our bodies. The experience is like that felt when one shits, pisses, sneezes or has an orgasm. It feels almost like singing itself.

Sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. This text is also partially about pleasure: the pleasure of living in the moment. That sacred, drug-induced, orgasmic moment where you aren’t thinking about the future or past, but are securely embedded in a series of ever unfolding now-now-now’s that open up into infinity.

It seems absurd that we can talk about the pleasure of music in the same way that we talk about drugs and sex. But for those of us who need music in that special way, it doesn’t seem strange at all. It’s the Cult of the Hit Song: that special song that you play over and over because it makes the hair stand up on the back of your neck. For fifteen minutes, it becomes the soundtrack of your life. I did it when I was a kid and I still do it now (most recently with “Saturday” by Yo La Tengo). The rush of pure pleasure still feels the same.[7]

The needles are pushed into the skin. Each one evokes a different sensation. This one is a prickle of pain, like a pin prick. This one feels cold, or hot. A throbbing ache. A carpenter’s nail breaking the skin. An electric shock. A tightening muscle. Distributed across the body, the array of pins creates a feeling of neither pain nor pleasure, but of INTENSITY. They remind you that the body is a field with which to receive information.

A bunch of young, hippie kids are sleeping in a Volkswagen van parked on my street. What kind of music do they listen to? What are their three or four life-defining albums? These hippie kids are young enough that they could have hippie grandparents. But of course they don’t. Families don’t exist anymore. In a world where youth is free, you are allowed to choose the parents you want — once you have disposed of your biological ones.

The youth revolution of the sixties was not a failure, but its meaning can be misinterpreted. It was about the liberation of the young. The young have been free ever since. It’s not so much that you can’t trust anyone over thirty, but that once you’re over thirty, you are no longer a recipient of the benefits of youth rebellion. You are no longer free.

Life is organized by sound.

Music is being segregated again. POP is quarantined from ALTERNATIVE. It reminded me of 1979, when confused record store clerks in Forest Lawn had ROCK and NEW WAVE and PUNK sections alongside COUNTRY and JAZZ. It’s curious what twenty years can do to the record bins. Now Elvis Costello, Sting and Laurie Anderson have slid into POP whereas The Jam, The Sex Pistols and Joy Division have been recuperated by ALTERNATIVE.

I dream of a record store where there is no segregation. Where black and white music come together. Where SOUL, HIP-HOP, TECHNO and ALTERNATIVE commingle with JAZZ, BLUES, COUNTRY and POP. Where you look for music according to its name, without having to understand genre.

I was worried that my taste in music would become frozen; that I wouldn’t successfully make the leap from the eighties to the nineties. I would remain a curious fossil playing the same records for decades to come. Not long ago, a reunited Supertramp came to town. Musically, the nineties were partially about reunions due to financial obligations. I am glad that I am not overly interested in the reunion of Fleetwood Mac, Supertramp, The Eagles, The Sex Pistols, Duran Duran and other musical franchises.[8]

Last week, I went and saw a Japanese pop band that blends Motown with Bollywood movie soundtracks; that combines contemporary dance music with French yé-yé. The audience was a mixture of Asians and whites, not everyone was young and I saw other queers there. The band didn’t really play. They just sang along with a bunch of video projections. Over the course of the evening the lead singer changed from one spectacular costume to another. I think this is what the new millennium will be like. Musicianship will be replaced by stage antics. Songwriting will be replaced by electronic spectacle. Authenticity will be replaced by pastiche and parody, and musical genres/eras/identities will be blended and distilled into strange unpredictable cocktails.

A deaf boy once told me that he danced by feeling the beat. Sound is a vibration. If you could sing higher than the highest note, it would become light. Lower than the lowest, your voice becomes touch. When I sing, everything converges in my chest. Lines emerge from my sternum and suck the world in. When I can feel the world resting in my chest, I know I am singing well.

Nelson Henricks

Spring, 2000

[1] In 1978 or ’79 I missed my chance to see Supertramp at McMahon Stadium in Calgary during the “Breakfast in America” tour. Two of my friends, Laura and Judy, went to the concert on acid. They came home exhausted and sunburned after sitting all day on the black rubber tarp that was stretched over the stadium’s infield. I think by then my infatuation with Supertramp had waned sufficiently that I didn’t regret missing the show. For the occasion, Judy had a t-shirt made at the mall. It was robin’s-egg blue and, in glittering individual letters, she had had the word “Supertramp” ironed onto it. Laura remarked that walking around with the word “Supertramp” stretched across your tits could be grossly misinterpreted. The t-shirt was relegated to the bottom drawer of her dresser, never to be seen again.

[2] I earned my criminal record changing the price tag on a copy of The Who’s Tommy (not the movie soundtrack, the original recording). I was charged for fraud, fingerprinted and fined as an adult, only three days after my eighteenth birthday. I lost my nerve for shoplifting after this.

[3] I think that The Wall, circa 1979/80, would have to be the fifth great album on The List.

[4] Or Exhibit B: Any number of young men who make public displays of themselves by driving around in cars with loud music blaring out the windows. Over the past several weeks, there have been repeated sightings of a middle-aged man in a convertible playing (and singing along with!) Crime of the Century at volume levels that exceed the limits of public decency.

[5] This is simultaneously profitable and terrifying for artists. Terrifying, because, in the most extreme cases, this transaction can be deadly (Charles Manson, Mark David Chapman, etc.).

[6] As evidence, I cite Todd Haynes revenge epic Velvet Goldmine. This indictment seems to be the only substantial content of the movie, and makes it easier to understand why Bowie didn’t allow his songs to be used in the soundtrack.

[7] Throughout the writing and revising of this text, this song has been updated. Here are some of the others that appeared in this paragraph: “Cut You Hair” by Pavement, Substitute” by The Who, “Ella Guru” by Captain Beefheart, “Music Sounds Better With You” by Stardust, “Tracy” by Mogwai, “Chicken with its Head Cut Off” by Magnetic Fields, “Out of Control” by The Chemical Brothers, etc., etc., etc.

[8] Pink Floyd are a sad example of “the-band-as-franchise”, spurting out a series of products that don’t seem to be the result of any creative endeavour. The necrophilic reunion of The Beatles was also fascinating in so far as it occurred in virtual space. The release of outtakes and butchered remixes featured in Anthologies 1, 2 and 3 seemed to destabilize The Beatles, revealing cracks and holes in the solid polished surfaces of their musical edifice. But that is another story.