Photo: Cheryl O’Brien

Lacuna brings together a series of works in diverse media inspired by the black page in The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. Written by Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy is a farcical autobiography. It was published in nine volumes between 1759 and 1767. The novel is highly experimental, exploring the limits of typography and print design. For example, in Book 1, Chapter 12, a page printed entirely black appears at a point in the story when a character named Yorick dies. On one hand, the black page can be understood as an overflowing of ink and emotion representing inexpressible grief. On the other, is an image of an open grave: an absence, a void.

Using Sterne’s black page as a starting point, Henricks developed several bodies of work. On one level, the project is an exploration of the history of modern art. Sterne’s black page both predates and anticipates 20th century monochrome, a history that traditionally begins with Malevich’s paintings Black Square (1915) and White on White (1918). Henricks excavates a prehistory of monochrome, one that originates in farce, rather than formal or spiritual concerns. On another level, the project is an examination of loss, and reckons with the limits of what can be expressed through language.

While working in the studio, Henricks began experimenting with a geometric motif: a succession of diminishing rectangles framed one inside the other. In architecture, a grid of sunken square boxes in a ceiling is called lacunaria. A lacunar ceiling both lightens and strengthens the structures they are used in. In literature, a lacuna is a missing portion of a book or manuscript. In this project, the lacuna becomes a means to reflect on loss, mourning, and memory. In the process, Henricks confronts the limits of language, and the role that transformation plays in processes of renewal.

LACUNA (BLACK PAGES)

Photo: Cheryl O’Brien

The project began with collecting multiple editions of Tristram Shandy published in different languages. The black pages were extracted and scanned. A black rectangle was added to the centre of the digital file. These images were then printed at almost human scale. Extraneous information––page numbers, volume and chapter headings, and even footnotes––are sometimes visible.

Photo: Cheryl O’Brien

Once scanned, the collected black pages were mounted on acid free paper. A black rectangle was silkscreened into the centre of one. Each print is original and unique.

LACUNA (ASH PHOTOGRAPHS)

Photo: Cheryl O’Brien

Once the pages were collected and extracted from the books, the question of what do to with the remaining volumes imposed itself. The artist decided to burn each book––minus the black page––one page at a time. The resulting ashes were placed on a flatbed scanner, overlaid with a white cardboard border. The ashes were scattered in the centre of the hand cut matte, and scanned at high resolution. The resulting images were printed large scale.

The ashes bear visible traces of ink. In some photos these traces are more discrete and harder to find. In other, they are large and readable: specific moments in the narrative emerge. In instances where dust and ashes exceed the hand-cut white matte, pictorial conventions break down. Taken together, the mattes and ashes function as crude facsimiles of the black page.

LACUNA (ASH PAINTINGS)

Photo: Cheryl O’Brien

The next step was to pulverize the ashes into a fine powder. This powder was mixed with either acrylic or oil-based mediums and applied to wood panels. The resulting monochrome paintings stand somewhere between being images and objects. Each painting has a unique colour: they range from pale grey to deep black. The texture of the surfaces varies greatly depending on the quality of the ash. This makes it difficult to reproduce them as photographs: they need to been seen and experienced directly. Like the ash photographs, these paintings function as representations or reproductions of the black page, made from the very substance of the books themselves.

LACUNA (PAINTINGS)

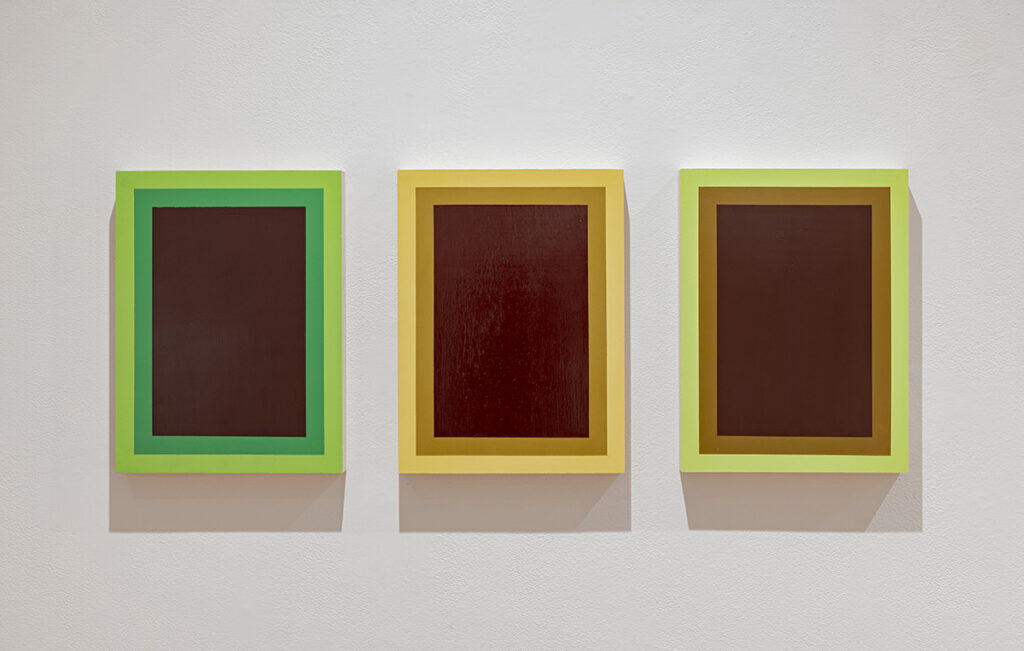

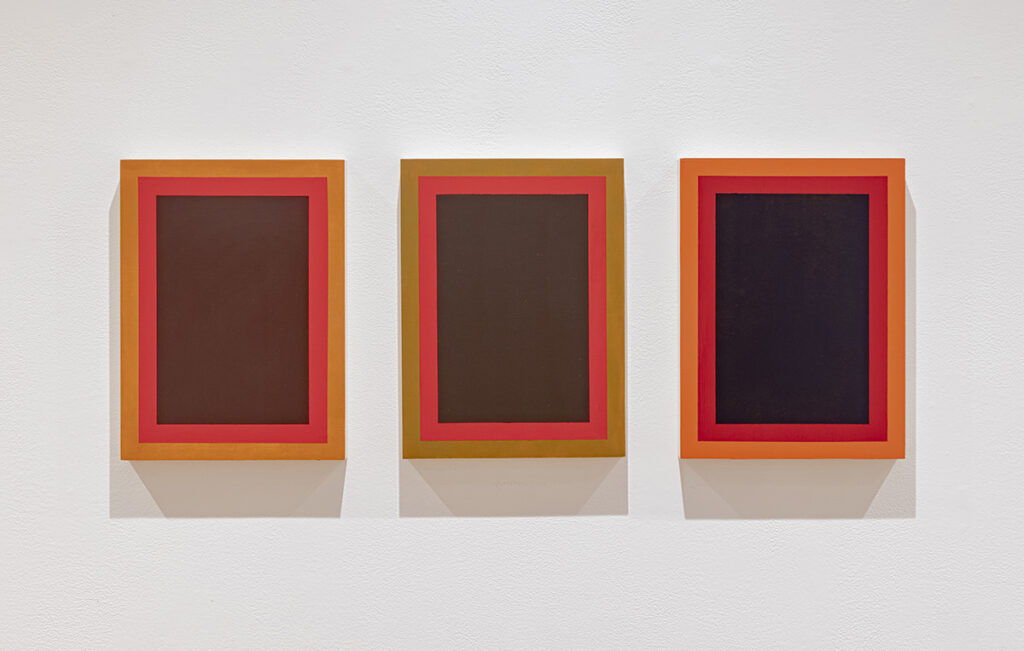

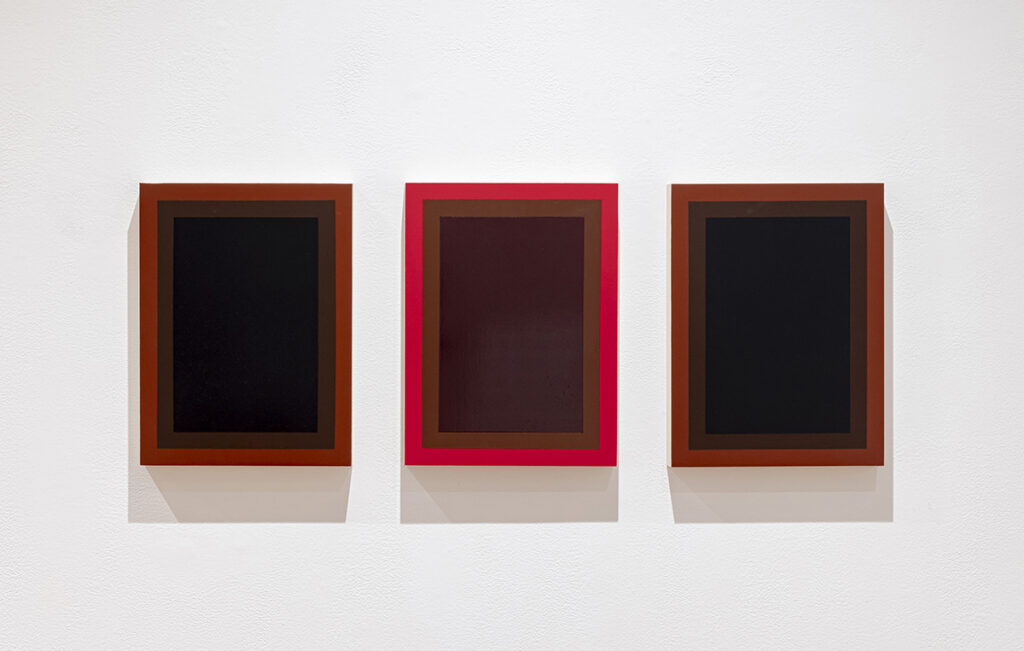

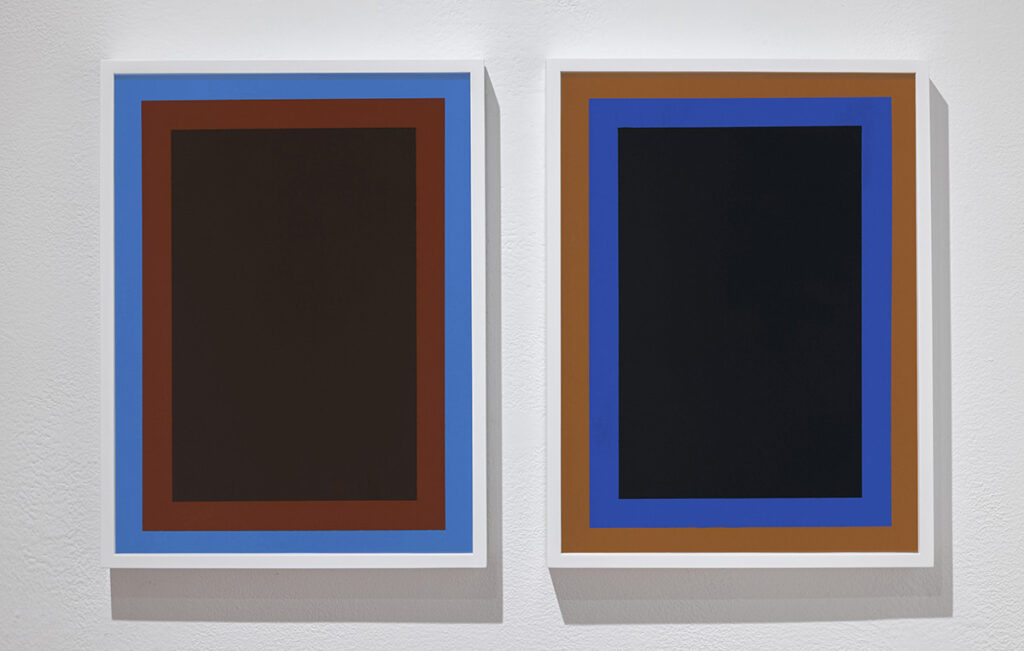

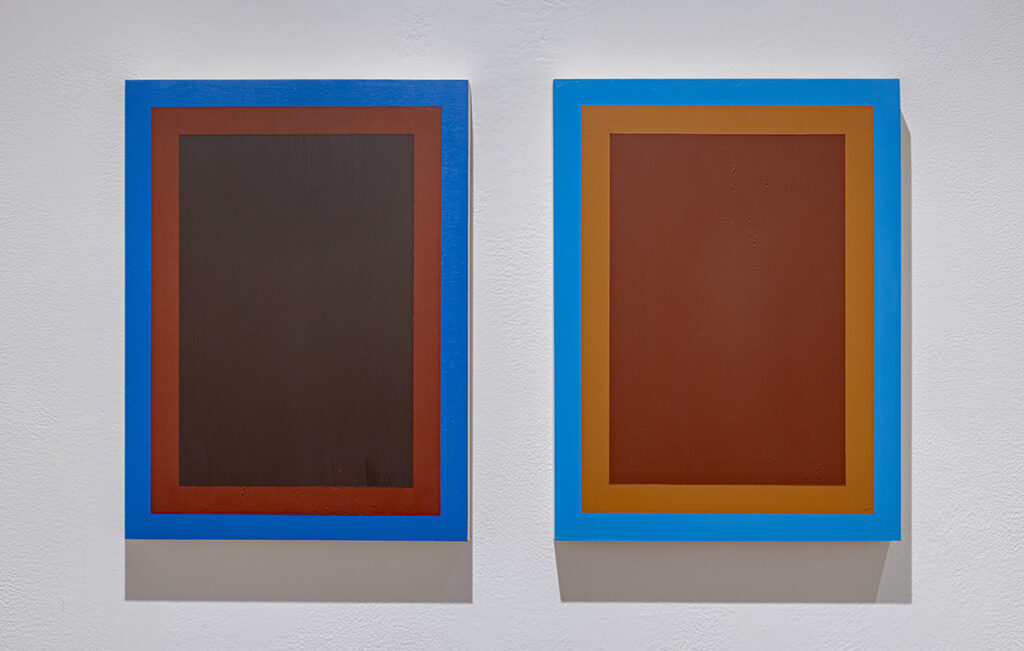

Photo: Cheryl O’Brien

Henricks’s mother was a landscape painter. When she died, the artist collected her remaining paints and had them shipped to Montréal. Using this “found” paint as material, he began reproducing the lacuna motif announced in the black page photographs and prints. The tri-coloured Lacuna paintings are executed on wood panel. Like the monochrome paintings, their status fluctuates between image and object. Henricks will continue creating these paintings until the entire supply of acrylic and oil paint is exhausted. Once all the paint has been used, the series will be complete.

Lacuna (Alas Poor Yorick!) exhibition at Paul Petro, 2019

Photos: Cheryl O’Brien