A Lecture on Art

Four channel video installation

Dimensions variable, 3:00, 2015

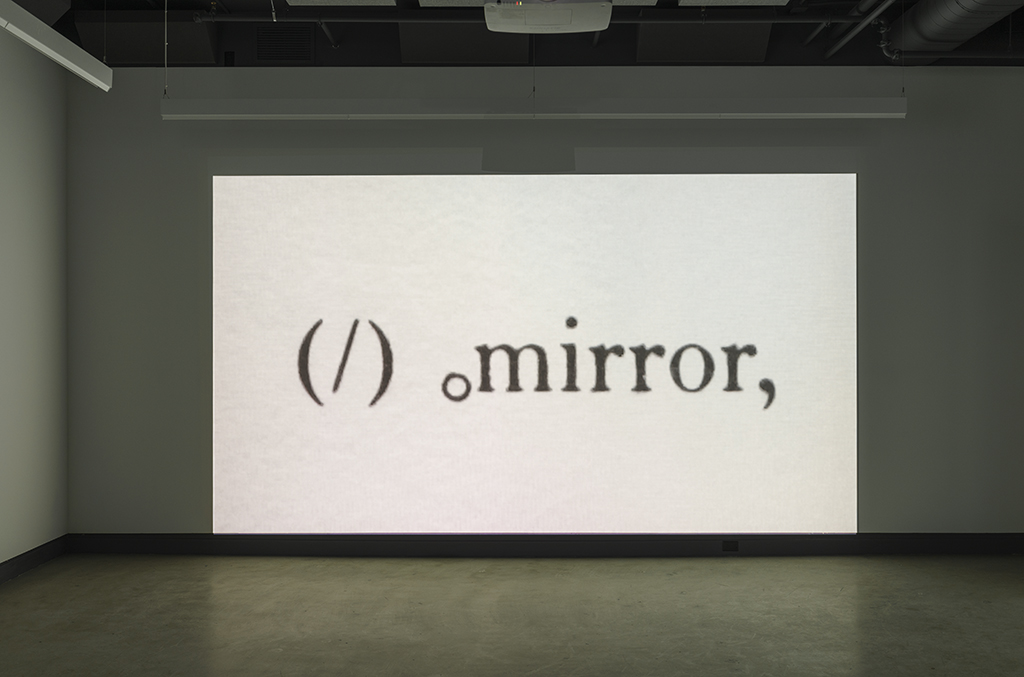

In the multi-channel installation A Lecture on Art, Nelson Henricks employs the medium of video to conjure the voice of Oscar Wilde. His starting point is a text written and presented by Wilde during his North American tour of 1882. Helen Potter, an American actress, attended one of Wilde’s talks, annotating his speech and capturing his voice on paper. In this work, Henricks reflects on what it means to record and reproduce sound and examines the place of aesthetics in art.

On the 1882 tour of Canada and America, Wilde was promoting the British Aesthetic Movement. Aestheticism blended art, craft, and interior design, and achieved a high degree of visibility in popular culture thanks to flamboyant figures such as Wilde and James McNeill Whistler. The Aesthetic Movement is widely regarded as the entry point for Théophile Gautier’s “art for art’s sake” dictum into British and North American art. Art need not exist for any other reason that to be beautiful. Wilde was here to spread this new and radical idea.

Inspired by French poets such as Baudelaire and Rimbaud, synaesthesia – cross modal sensory perception exemplified by phenomena such as ‘hearing colour’ – was important to Aesthetic artists. The stimulation of one sense through another produced a layering of responses, deepening the viewer’s experience. Musical references abound in Aesthetic painting, both in imagery and titles (famously, in Whistler’s many Nocturnes and Harmonies). Walter Pater’s declaration that “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music” is the signature phrase of Aestheticism.

During the 1882 tour, the American actor and performer Helen Potter attended Wilde’s lecture, presumably in New York. She annotated Wilde’s speech in order capture his cadence and inflection. The annotated text was later published in Impersonations (1891), a book in which she documented the speech patterns of 26 public figures. Potter was a minor celebrity in the United States in the 1890’s, performing her depictions of writers, actors and political activists such as Susan B. Anthony to wide audiences. In a chapter entitled To Students: How to Prepare for Impersonations, she provided detailed instructions on how to study lecturers and actors.

Potter’s book exists as a trace of her performances and as an instruction manual for those wishing to create a convincing impersonation. Her annotation of Wilde’s speech functions as a visual representation of sound, a kind of visual score. It is important to recall that her performances took place in a cultural context in which communications technologies such the telegraph, the phonograph, and the telephone were emerging. Potter’s work participates in the changing social attitudes towards the presence of disembodied voices. She writes:

“[T]he works of artists in clay, marble, and iron, and on canvas are enduring, and eagerly sought for. But the most wonderful of all, the power of the human voice, goes to the winds and is lost forever. Seek as we may, the winds tell us not of these masters of oratory and song. Their master tones reach not our ears, and we know of their power only by tradition. Now, with what skill we have, we will endeavour to perpetuate some of the work of our own time. The work of a few of the best orators and artists of this age and people, we will record, as accurately as our methods of annotation will allow.”